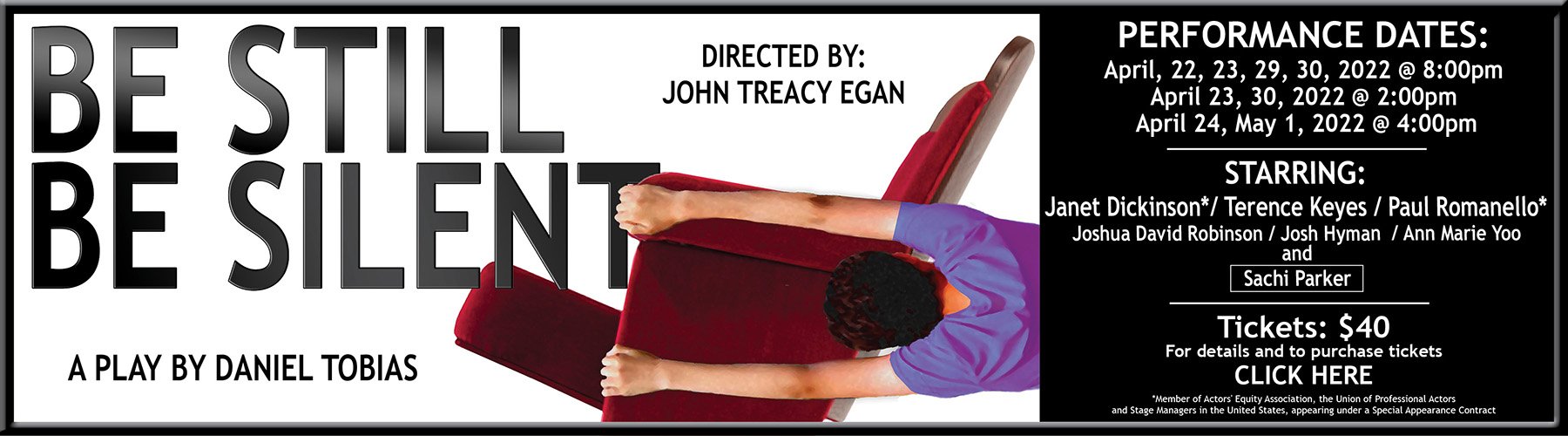

Be Still Be Silent: A Worthwhile World Premiere from SOOP Theatre Company

By Gary Skidmore

Is it appropriate to bring an autistic teenager, who has difficulties expressing their emotions in ways that others may consider “socially acceptable”, to see live theatre? Inspired in part by a real-life outburst by an autistic teen at a Broadway performance of The King and I, that is the question that sets Daniel Tobias’ intelligent and thought-provoking new play Be Still Be Silent, currently being given its world premiere by SOOP Theatre Company in Pelham, into action.

It is also the question facing Eugene Thomas (Paul Romanello), on the opening night of the new Broadway play he is directing. The teenager in question is Danny (Joshua David Robinson), who is equally fascinated by the works of Tennessee Williams and Disney animation, and who expresses emotion through a stuffed Olaf from “Frozen”. Danny is the nephew of Cynthia (Janet Dickinson), Eugene’s costume designer girlfriend, who has invited Danny to the opening as her “plus one”, much to the horror of acerbic theatre critic Peter Grey (Terence Keyes). As they gather in Eugene’s apartment before heading to the theatre, all three characters initially seem absorbed only by their immediate needs (such as Eugene dealing with last minute phone calls from his difficult leading lady). Danny’s presence allows Mr. Tobias to reveal the deeper stakes, both professional and personal, facing these complex characters who are not as one-dimensional as they might initially seem.

Director John Treacy Egan has assembled a fine cast who more than do justice to these characters. As Danny, Mr. Robinson faces the difficult task of portraying the autistic traits of the character without crossing the line into caricature, and does so successfully. He makes admirable use of both his voice and physicality, particularly when rapidly (and impressively) rattling off a list of Tennessee Williams plays in chronological order. Mr. Romanello shows genuine warmth toward and desire to include Danny, even as he knows Danny’s presence could have an impact on the success of his show. Mr. Keyes, in what could easily be a one-note character, makes the most of both Mr. Tobias’ best barbs, and the opportunities to soften his character’s sharp edges. This is especially so as he develops a bond with Danny, yet remains fiercely aware of how fragile the illusion of theatre truly is. Ms. Dickinson’s Cynthia, perhaps the true pivot point of the show connecting all of the other characters, plays tenderness and loyalty toward Danny, desperation to help Eugene, and anger at Peter deftly, without resorting to histrionics. Mention also needs to be made of Josh Hyman as Otto, the building’s doorman, with his own connection to autism. Initially wry and friendly, he is truly moving when he gets a chance to speak his mind, and lets the other characters know there are many more challenges to dealing with an autistic child among the less privileged than theatre attendance.

Rounding out the cast are Sachi Parker as Danny’s mother Jo and Ann Marie Yoo, as the characters Arinya Wong, an actress in The King and I at the aforementioned performance and Bonnie Haze, an outspoken, edgy NY actor. Jo, who is dying of cancer, delivers moving monologues about raising and loving an autistic child, about not being able to see her son grow into a man and about the others who will look after him. Ms. Yoo completes a truthful study in contrasts, as she reacts kindly and with sympathy to the outburst from a paying audience member while she is onstage (as Arinya), but less so when awakened at 3 a.m. by Otto’s daughter (as Bonnie).

As precise and realistic as each individual performance is, Mr. Egan brings them together smoothly into a cohesive whole, especially as emotions run high and true motivations come to light in Act II. He also makes excellent use of the well-designed set (by Reilly Rabitaille immediately evoking the exact kind of sleek, modern Manhattan apartment Eugene would live in) in the relatively small space.

Be Still Be Silent does not deal in easy subject matter. While it ultimately provides its answer to the question it poses, it is not done in a preachy or judgmental way. It goes to great lengths to be fair and does so with truth and honesty. Audience members are likely to see themselves in both of Ms. Yoo’s monologues. Mr. Romanello, at the top of Act II, muses on the event in his character’s life that led to his career in the theatre, and how the outburst of an autistic audience member could have changed that forever. Perhaps his choice came at the cost of denying someone access to the theatre. “Whose experience”, he asks, “is worth more”? Regardless of the answer, this is a piece worth seeing.